Chainsaw

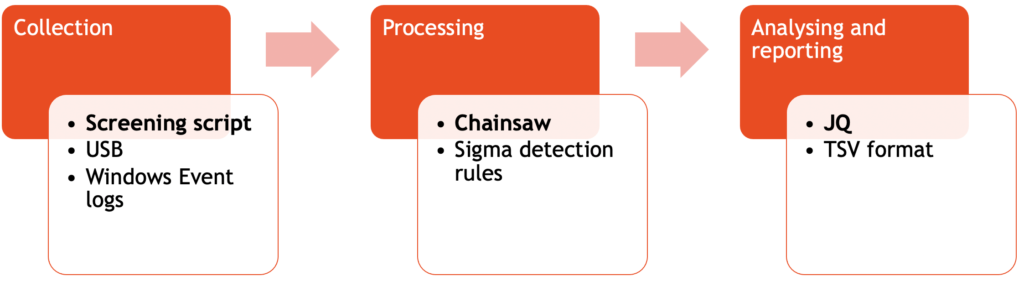

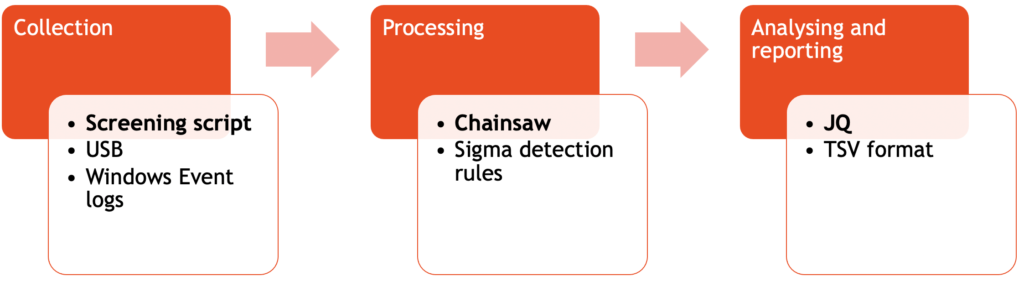

Chainsaw is a tool to rapidly search through large sets of Windows Event logs. In this post I briefly go through the steps that I take to collect, process and analyse logs from different Windows machines and then use them for analysing Windows Event logs. Obviously it’s always better to use centralised logging and apply your detection techniques centrally but unfortunately this isn’t always possible.

Installation

Although Chainsaw is available as a binary package I compile it from source.

git clone https://github.com/countercept/chainsaw.git

cd chainsaw

cargo build --release

After compilation you can find the binary in target/release.

./chainsaw -h

Detection rules

Older versions of Chainsaw included the detection rules as sub packages but now you need to add these yourself. It’s a one step process, you just need to clone the Sigma repository.

git clone https://github.com/SigmaHQ/sigma.git

Now that the environment is configured, it’s time to collect and process the logs.

Collect and process Windows Event logs

Collect the Windows Event logs

I use a small audit screening script (available on GitHub) that not only collects Windows Event logs, it also does live forensics. For the purpose of this post, you only need these lines to collect the logs.

set script_dir=%~dp0

set aud_dir=%script_dir%audit_%COMPUTERNAME%

mkdir %aud_dir%

cd %aud_dir%

xcopy /E/H/C/I "%SystemRoot%\System32\Winevt\Logs" logs

As a side note: I run the entire script from clean (formatted per system) USB keys on the target systems. The live forensic data is then afterwards analysed on a “master” system. Using Chainsaw is just one of the steps in this analysis.

Process the Windows Event logs

Processing the logs can be done in two ways,

- Either you search for a specific string or event ID;

- or, you run the detection rules against the event logs and hunt for anomalies.

Searching is useful if you already know what you’re looking for. For example listing the user authentication actions, filtering for processes that have started or tracking when systems have been locked (event ID 4800) or unlocked. I use these options when searching with Chainsaw:

- –json and –output to have JSON formatted output to a file;

- With -t you specify a tau expression to search for.

./chainsaw search --json -t 'Event.System.EventID: =4800' ~/screening/audit_system1/logs/* --output ~/screening/audit_system1/processed_search_4800.json

And although the search function is very flexible, the real power of Chainsaw lies in applying the various detection rules against your dataset. To do this you have to start it with the hunt keyword and provide these parameters:

- –json and –output to have JSON formatted output to a file;

- –mapping refers to the mapping file included in the Chainsaw repository to link Sigma rules to the Event logs;

- –sigma points to the earlier cloned repository with the Sigma rules. Make sure you point it to the rules directory in that repository;

- The final parameter points to the Windows Event log. You can specify one file, or multiple files at once. If you run the detection against multiple log files of different types (channels) then verify that an alert for an Event ID is relevant for that log file. For example the Event ID 100 exists in IIS, DNS and the Certificate Service but has a different meaning depending on its log source.

./chainsaw hunt --json --output ~/screening/audit_system1/processed_hunt.json --mapping ../../mappings/sigma-event-logs-all.yml --sigma ../../../sigma/rules/ ~/screening/audit_system1/logs/*

Analysing the Windows Event logs

The results of hunting with Chainsaw are JSON files with the matches for the detection rules. Generally there are two types of matches: either an individual match or aggregates of a match. In the JSON file they are represented as follows

{

"group": "Sigma",

"kind": "individual",

"document": {

"kind": "evtx",

"data": {

{

"group": "Sigma",

"kind": "aggregate",

"documents": [

{

"kind": "evtx",

"data": {

In order to make the resulting JSON file a bit more human readable, I use JQ to format the output.

cat ~/screening/audit_system1/processed_hunt.json | jq . > ~/screening/audit_system1/processed_hunt-format.json

Manually going through the JSON result files is doable when there are not that many matches. In most cases though this is very time consuming. In a next step I rely again on JQ to filter out the fields that I care about. I use the result as the first indication of elements that require further inspection. The fact that you can format the output with JQ in a table format also makes it directly usable for reports (here output via JQ to TSV is used, but you can also use output to CSV).

There are two big “blocks” in the JSON event per detection. One refers to the actual event data (available via .document.data.Event.EventData) and another block referring to the system data (available via .document.data.Event.System). EventData contains the more specific information, whereas System holds the timestamp and device information.

cat ~/screening/audit_system1/processed_hunt-format.json | jq -r '.[]

| {name, eventid:.document.data.Event.System.EventID,timestamp, computer:.document.data.Event.System.Computer,process:.document.data.Event.EventData.ProcessName, user:.document.data.Event.EventData.TargetUserName}

| [.timestamp,.computer,.eventid,.name,.process,.user]

| @tsv'

2022-04-28 MYSERVER 4616 Unauthorized System Time Modification D:\\usr\\file.exe

2022-04-28 MYSERVER 4625 Account Tampering - Suspicious Failed Logon Reasons D:\\Program Files\\file.exe Services

2022-04-28 Multiple Users Failing to Authenticate from Single Process

2022-05-03 MYSERVER 4692 DPAPI Domain Master Key Backup Attempt

(output trimmed and redacted)

Now, depending on what I get as initial results, there might be a need to add additional fields to the output.

cat ~/screening/audit_system1/processed_hunt-format.json | jq -r '.[] | {name, eventid:.document.data.Event.System.EventID,timestamp,

computer:.document.data.Event.System.Computer,

process:.document.data.Event.EventData.ProcessName,

user:.document.data.Event.EventData.TargetUserName,

rulename:.document.data.Event.EventData.RuleName,

remote:.document.data.Event.EventData.RemoteAddresses,

path:.document.data.Event.EventData.Path}

| [.timestamp,.computer,.eventid,.name,.process,.user,.rulename,.remote,.path]

| @tsv'

Conclusion

The approach of collecting the logs with screening script and then analysing them with a combination of Chainsaw, Sigma and JQ is sufficient for me to get a first view on what has happened on specific devices. There is still a bit of manual post-processing work and all depends on the Sigma rules that are applied, but in general this approach works quite well and has provided me a lot of valuable results.