Website compromised

I recently had to handle a case where a website development company was hacked. This post describes some of my findings during the investigation.

Incident intake

All of the company websites were hosted on one virtual server running Linux. Most of these websites were WordPress powered. The management of the server was done via DirectAdmin, updating of the web files happened via FTP.

The incident was brought to the attention of the company because they received complaints that some of their sites became unavailable. Additionally their hoster also complained about massive spam runs being conducted from their server.

I received the web logs and a copy of the files available on the webserver. Unfortunately the logging did not contain the content of the POST requests. This is not unusual but it would have helped further investigation.

This post only focuses on one website compromise. The company suffered from multiple compromises on different websites but I only take this one example to share my process.

Timelines and timestamps

Whenever dealing with an incident it’s important to keep track of what happened when and by whom. The best way to do this is via a timeline. It does not matter what tool you use to put together the timeline, even using pen and paper is a valid option. The most important thing is that the timeline needs to be able to help you understand how the attack took place and what sequence of events lead to the attack.

For this exercise I used a simple Excel sheet to construct the timeline. I noted the source IP, the timestamp, the action, the browser information and some comments.

A note about timestamps. When re-constructing events during an intrusion you also have to check if the machines you are investigating are NTP-synced. If this is not the case you have to adjust the timestamps of the different events. If you don’t do this you might draw the wrong conclusions, thinking that event A happened before B, based on a timestamp that was out of sync.

In this exercise, all the logs are sourced from the same machine and the goal was merely to know what events lead to the attack. Even if the machine was not NTP-synced, this would not influence my findings. Nevertheless, it’s worth noting that the host was NTP synced and set to UTC.

The host was set to UTC but the Apache access logs were in CEST. This difference is important when verifying the timestamps of the local files with the timestamps of the web requests that lead to the creation of these files (I had to adjust the timestamp with 2h).

Constructing the timeline of attack

The compromise I focused on (as said, the company felt victim to multiple sites being compromised) was a website running on WordPress. WordPress is one of the attackers preferred attack platforms because there are a lot of unmaintained and unpatched WordPress sites.

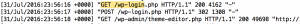

WordPress login

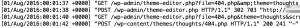

At 31-Jul the logs showed a request to wp-login.php, this is the WordPress login page. After the initial GET request there was a POST request and again a successful GET request to a file in /wp-admin/. Basically this means that the attacker was able to login successfully to WordPress.

After the login the logs show that the attacker went to the WordPress theme editor. The theme editor is a simple text editor in WordPress located at Appearance -> Editor. It allows you to modify WordPress theme files from the admin area, meaning you can adjust code that gets executed by the webserver via the (admin) web interface.

The log lines show that the attacker used the theme editor to change the 404.php page in the theme “thoughts”.

What was changed in this page? The attacker left the page intact but added one line of code that does a PHP eval of the POST parameters ‘dd’.

Subsequent to the change the logs showed other POST requests going to the 404.php page, both from the IP that did the initial login and from other IPs.

There’s nothing wrong with the WordPress theme that was installed. The attacker did not abuse a vulnerability in WordPress, a plugin or in the theme. The attack consisted of using valid WordPress credentials and then changing the web code of a theme. Things any ordinary WordPress administrator can do.

Inserting the PHP eval (remember, the eval function allows execution of arbitrary PHP code) allowed the attacker to send arbitrary code to the server. Disabling eval (and other potentially dangerous functions) can be done by using http://php.net/manual/en/ini.core.php#ini.disable-functions. This was not the case in this setup.

File uploads

So what did the attacker(s) tried to achieve by sending data to the PHP eval function? Based on the log files and find files on the system they tried uploading another PHP file (or instruct the server to download a file from another location) that they could then use to get more control on the host. However there was not one file with a change timestamp that corresponded with the time of the web requests. This doesn’t mean that a file was not created, the file can be changed afterwards leading to an updated file timestamp.

The logs then showed subsequent POST requests to 404.php. This probably indicates that one of these subsequent requests modified the initially created file. As a reminder, you can use the Linux stat command to get the last access, last modified and last change date (the difference between modified and change is that modify concerns ‘content’, change concerns a change in the meta data, for example permissions).

WSO shells

I found three files that had a modify timestamp that corresponded with the subsequent (last) POST requests. One of these files had obfuscated content, starting with

<?php $auth_pass="";$color="#df5";$default_action="FilesMan";

$default_use_ajax=true;$default_charset="Windows-1251";preg_replace("/.*/e","\x65\x76\x61\x6C\x28\x67\x7A\x69...

I used online tools to deobfuscate the content and then prettify the code.

First I used PHP Decoder to get the deobfuscated PHP code. I then used the output of this tool to beautify the code via PHP Beautifier. This resulted in readable PHP code. The code contained a version definition string

@define('WSO_VERSION', '2.5');

“WSO” gives away that this concerns the WSO Web Shell. This web shell provides various features to an attacker like browsing the entire server, uploading and executing code and performing database actions.

The “basic” version of WSO requires attackers to submit a password (handled via ‘function wsoLogin()’) before being able to enter the shell. I also found another WSO shell with the version ‘2.5 lt’. This shell did not require a password but a cookie being set.

The result of the different uploads of various webshells indicated that the attacker had full control on the webserver. Reconstructing the POST log entries I could find leads to various files that were uploaded after the install of the webshell, some of them were spambots

Conclusions

Typically when you look at WordPress hacks you think about outdated versions.

This site was running the latest WordPress (4.5.3) with all plugins updated. This attack did not consist of exploiting a vulnerable version. Based on the login sequence in the logfiles it is relatively safe to assume this attack was performed via weak access credentials.

I did not ran any of the samples that found in a sandbox but used online tools like

to get hold of readable PHP code.

There’s a risk when using these online tools. Careful attackers might be able to snoop on the popular online tools to get notified that there attack has been spotted (typically this is for example the case with files uploaded to Virustotal). However in this case it was safe to assume that the attackers were not worried about this. They did not tried to cover their actions in any way on the server.

Based on the different artifacts that were found during the upload of files (various version of WSO) and the weblogs I can conclude that this compromise did not involve an exploitation of a vulnerable WordPress website. The attack consisted of the abuse of weak login password for a WordPress user. This user account then was allowed to change the included web theme, leading to the upload of various webshells. These webshells allowed the attacker further control of the webhost.

The initial staging of the attack could have been prevented by disabling the dangerous PHP eval function. This was not the case for this attack. However it’s not that un-common to see eval enabled by web hosters, most often because their customers otherwise start complaining that their web app “does not work”.