Dridex hunting

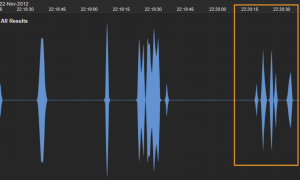

Increase of campaigns

Dridex, the multifunctional malware package that leverages macros in Microsoft Office to infect system has seen an increase in the number of campaigns.

What is Dridex?

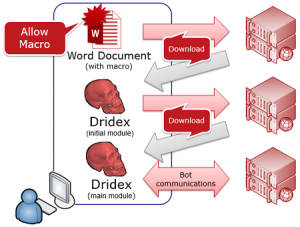

Dridex will first arrive on a user’s computer as an e-mail with an attached Microsoft Word document. If the users opens the attachment (with macros enabled) then a macro embedded in the document triggers a download of the Dridex banking malware, enabling it to get installed.

See for example in an article from JP-CERT.

This means that if we can prevent the download of the 2nd phase we can prevent the infection with the downloaded Dridex malware. We will still have to clean-up the host (from the harm that was done by running the document macro) but at least the banking malware is stopped from further execution.

There are some preventive protection measures that you can take to be protected against an infection. But having multiple layers of defense is the best way to have your network protected.

Stop the infection

So how do you stop the download? Simple : by blocking access to the download site (and additionally block access to sites to which full infected machines report their findings). The problem that remains is : where do you get the list of download sites (or IPs)?

Ideally you get such a list via sharing threat information, possibly through a sharing platform like MISP. But what do you do if you do not have access to a sharing platform?

Hunting for Dridex C2 info

Unfortunately there’s no such Dridex C2 Blocklist (and read in the conclusions why that’s not entirely a bad thing). So you’ll have to get the information yourself, from various sources. I listed a couple of the sources below that you can use to build your own blocklist.

Dridex sources

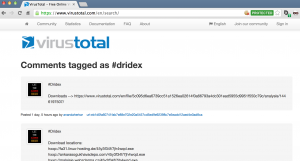

VirusTotal

The first place to look for Dridex information is at VirusTotal. It allows you to search for all comments that have a tag, in this case #dridex.

VirusTotal has an API. You can look up IP or domain information but unfortunately it does not support an option to search in the comments.

Because of this, using VirusTotal for setting up a blocklist is not scalable. It’s good for getting updated rules for specific cases but you’ll have to copy/paste the indicators yourself.

CyMon

The next resource I had a look at was CyMon. It is a tracker of open-source security reports about phishing, malware, botnets and other malicious activities. Unfortunately it has no support for string searches.

Because CyMon does not allow you to search for a string related to “dridex” it is not an option for contributing to a blocklist.

Open Threat Exchange

The Open Threat Exchange – OTX from Alienvault allows security researchers and threat data producers to share research and investigate new threats. It has a web interface and an API interface.

The web interface allows you to export indicators in CSV, OpenIOC or STIX format.

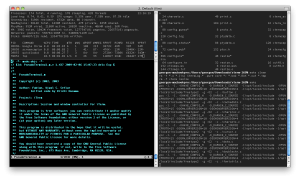

The script below allows you to download all the IPv4 indicators for Dridex (at least events with the tag dridex). Just be sure to insert your own API key.

#!/usr/bin/env python

from OTXv2 import OTXv2

from pandas.io.json import json_normalize

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

import re

import os

import sys

import traceback

import argparse

import datetime

import dateutil.relativedelta

otx = OTXv2("myapi")

previousmonth= (datetime.datetime.now() + dateutil.relativedelta.relativedelta(months=-1)).strftime('%Y-%m-%d')

#pulses = otx.getsince(previousmonth, 100)

pulses = otx.getall()

output = []

for pulse in pulses:

n = json_normalize(pulse)

name = n["name"][0]

indicators = n["indicators"]

tags = n["tags"][0]

created = n["created"][0]

indicator = indicators[0]

for ind in indicator:

if ind["type"] == "IPv4":

for tag in tags:

if tag == "dridex":

print "%s ; %s ; %s ; %s " % (ind["indicator"], created, name, tags)

output.append( { 'indicator': ind["indicator"], 'created': created, 'name': name, 'tags': tags} )

#print output

Unfortunately OTX does not have a lot of updated information for Dridex. If you filter for the most recent events (in the code, you have to switch comments for the line with ‘getsince’) then often you get no results. So extracting Dridex IP information from OTX returns either no or at least older information.

OTX is a good option to automatically add indicators to your blocklist. Unfortunately some of the information is older.

Feodo Tracker

I then used Feodo Tracker. It is a botnet C&C servers tracker, servers related to Dridex are listed version D in their overview.

The IP-blocklist is downloadable as a text file.

########################################################################## # Feodo IP Blocklist # # Generated on 2015-10-31 15:03:43 UTC # # # # For questions please refer to https://feodotracker.abuse.ch/blocklist/ # ########################################################################## # START 103.16.26.228 103.16.26.36

The blocklist is also downloadable as a Snort rules file or as a Suricata rules file. The list is fairly regularly updated but also contains some older records (this might cause an issue when IPs are reused).

The Feodo tracker is a good option for automated and updated information.

Malware Domain List

The site Malware Domain List has a list of (older) Dridex IP information. The list for Dridex is not downloadable as a text file.

Because of the outdated information, the list at MDL will not contribute that much to a blocklist.

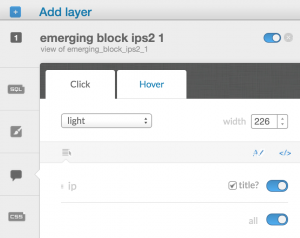

Emerging Threats

The rulesets at Emerging Threats provide you a list of block rules that can be used with Snort or Suricata.

The rulesets from Emerging Threats provide a good source if you run an IDS (Snort or Suricata).

Conclusion

None of the tested sources provided a comprehensive and easy accessible list of Dridex C2 IP information.

| Dridex | via API | via GET | Recent | IP list | IDS | |

| VirusTotal | ||||||

| CyMon | ||||||

| OTX | ||||||

| Feodo | ||||||

| Malware Domain List | ||||||

| Emerging Threats |

Although a public IP blocklist to protect against further Dridex malware download would make sense it can also introduce other problems. Similar as to VirusTotal were attackers can monitor if new pieces of malware get detected by AVs you give away when an IP, part of the attackers’infrastructure, has been detected. Worst case, the malware gets updated instructions to contact another host, one that is not yet on the blocklist.

If you want to build your own blocklist then

- start with the information that you get from Feodo tracker

- combine that information with some manual input from VirusTotal

Ideally you can share your output via a sharing platform as MISP.