Train your incident response team

This is the third part in a post describing how to train your team for incident response and incident investigations.

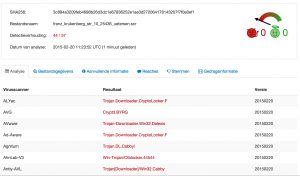

The first part for training incident response and incident investigations covered how to analyze the e-mail headers and information in a suspicious e-mail. The second part analyzed the attachment which turned out to be a CryptoLocker.F variant.

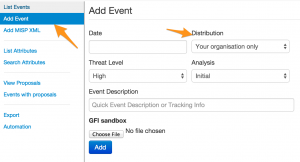

Networked VM

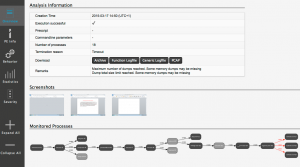

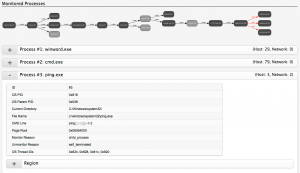

The last step of my analysis involved executing the CryptoLocker virus in a fully networked VM. After resetting the Windows XP virtual machine I enabled networking and started capturing the network packets.

It took a couple of minutes before I started to notice unusual behavior but then this showed up in the virtual machine

The notice is in Dutch, basically saying that your files are now locked and you have 96 hours to do a payment. This means the machine is now fully infected.

I do not know why the notice was in Dutch. Maybe because the analysis was done from an IP that is geo-located in Belgium (Flanders) or because of the fact that the malware was maybe specifically aimed at Dutch speaking users?

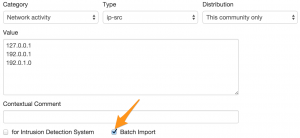

Network capture

The network traffic was captured in a pcap file. This allows me to have a detailed look at the connections without having the need of keeping the machine running. In the capture below, 192.168.171.146 is the infected Windows machine and 192.168.171.2 is the default route for that machine.

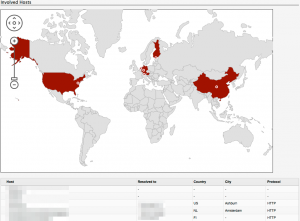

The first thing I noticed in the capture was a DNS query for the domain smartoptionsinc.com with a DNS response of 216.70.228.110 (both located in the US). Immediately after the DNS request, there was a request to 216.70.228.110 on tcp/443 (https). During the https conversation there was a request for the PTR record of 216.70.228.110 (110.228.70.216.in-addr.arpa). I’m not sure if the request for the PTR record was caused by the malware or because of normal operation of the Windows host.

19:21:10.265447 IP 192.168.171.146.1321 > 192.168.171.2.53: 23427+ A? smartoptionsinc.com. (37)

19:21:11.031868 IP 192.168.171.2.53 > 192.168.171.146.1321: 23427 1/13/0 A 216.70.228.110 (264)

19:21:11.033897 IP 192.168.171.146.1322 > 216.70.228.110.443: Flags [S], seq 3369729607, win 64240, options [mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK], length 0

19:21:11.192678 IP 216.70.228.110.443 > 192.168.171.146.1322: Flags [S.], seq 1816156004, ack 3369729608, win 64240, options [mss 1460], length 0

...

19:21:11.542592 IP 216.70.228.110.443 > 192.168.171.146.1322: Flags [P.], seq 919:970, ack 261, win 64240, length 51

19:21:11.583938 IP 192.168.171.146.1323 > 192.168.171.2.53: 13061+ PTR? 110.228.70.216.in-addr.arpa. (45)

19:21:11.643981 IP 216.70.228.110.443 > 192.168.171.146.1322: Flags [P.], seq 919:970, ack 261, win 64240, length 51

...

19:21:11.925041 IP 192.168.171.2.53 > 192.168.171.146.1323: 13061 1/6/0 PTR 216-70-228-110.static-ip.telepacific.net. (211)

Downloading the certificate information revealed this might be a Synology device.

openssl s_client -connect 216.70.228.110:443

subject=/C=TW/ST=Taiwan/L=Taipei/O=Synology Inc./OU=FTP Team/CN=synology.com/emailAddress=product@synology.com

issuer=/C=TW/ST=Taiwan/L=Taipei/O=Synology Inc./OU=Certificate Authority/CN=Synology Inc. CA/emailAddress=product@synology.com

There have been reports of SynoLocker Ransomware Affecting Synology DiskStation. I could not confirm if this was the case for this host but it does not seem to be unlikely. Also remember that in the previous part I noticed that the website of smartoptionsinc.com (hosted at 216.70.228.110) was in an abandoned or at least in a “not finished” state. This makes it more likely to be a target.

19:21:12.468442 IP 216.70.228.110.443 > 192.168.171.146.1322: Flags [P.], seq 970:1558, ack 442, win 64240, length 588

19:21:12.470807 IP 216.70.228.110.443 > 192.168.171.146.1322: Flags [FP.], seq 1558:1624, ack 442, win 64240, length 66

19:21:12.471526 IP 192.168.171.146.1322 > 216.70.228.110.443: Flags [.], ack 1625, win 64240, length 0

19:21:12.472408 IP 192.168.171.146.1322 > 216.70.228.110.443: Flags [R.], seq 442, ack 1625, win 0, length 0

Subsequent similar network behavior

The network communication with smartoptionsinc.com consisted of

- Doing a DNS query for the domain

- Receiving the DNS reply

- Starting a connection on tcp/443 (https) to the IP

- Requesting the PTR record for the IP

Having a look at the other three listed domains revealed the same network pattern.

ppc.cba.pl

19:21:17.479276 IP 192.168.171.146.1327 > 192.168.171.2.53: 24966+ A? ppc.cba.pl. (28)

19:21:17.517892 IP 192.168.171.2.53 > 192.168.171.146.1327: 24966 1/13/0 A 95.211.144.65 (255)

19:21:17.519091 IP 192.168.171.146.1328 > 95.211.144.65.443: Flags [S], seq 3421975270, win 64240, options [mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK], length 0

19:21:17.545014 IP 95.211.144.65.443 > 192.168.171.146.1328: Flags [S.], seq 3198389694, ack 3421975271, win 64240, options [mss 1460], length 0

...

19:21:17.615556 IP 192.168.171.146.1329 > 192.168.171.2.53: 56835+ PTR? 65.144.211.95.in-addr.arpa. (44)

The certification information was as follows

subject=/OU=Domain Control Validated/OU=PositiveSSL/CN=cba.pl

issuer=/C=GB/ST=Greater Manchester/L=Salford/O=COMODO CA Limited/CN=PositiveSSL CA 2

cargol.cat

19:21:22.649647 IP 192.168.171.146.1330 > 192.168.171.2.53: 15239+ A? cargol.cat. (28)

19:21:22.803797 IP 192.168.171.2.53 > 192.168.171.146.1330: 15239 1/13/0 A 217.149.7.213 (255)

19:21:22.804598 IP 192.168.171.146.1331 > 217.149.7.213.443: Flags [S], seq 3319478930, win 64240, options [mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK], length 0

19:21:22.858941 IP 217.149.7.213.443 > 192.168.171.146.1331: Flags [S.], seq 1829101853, ack 3319478931, win 64240, options [mss 1460], length 0

...

19:21:23.560461 IP 192.168.171.146.1332 > 192.168.171.2.53: 37378+ PTR? 213.7.149.217.in-addr.arpa. (44)

19:21:23.622886 IP 192.168.171.2.53 > 192.168.171.146.1332: 37378 1/6/0 PTR vm7213.filnet.es. (186)

The -expired- certificate had this information

subject=/C=ES/ST=Catalunya/L=Barcelona/O=Tirabol Produccions

issuer=/C=ES/ST=Catalunya/L=Barcelona/O=Tirabol Produccions

bikeceuta.com

19:21:28.061769 IP 192.168.171.146.1333 > 192.168.171.2.53: 57220+ A? bikeceuta.com. (31)

19:21:28.090268 IP 192.168.171.2.53 > 192.168.171.146.1333: 57220 1/13/0 A 91.142.215.77 (258)

19:21:28.090787 IP 192.168.171.146.1334 > 91.142.215.77.443: Flags [S], seq 1209465814, win 64240, options [mss 1460,nop,nop,sackOK], length 0

19:21:28.160456 IP 91.142.215.77.443 > 192.168.171.146.1334: Flags [S.], seq 4167533275, ack 1209465815, win 64240, options [mss 1460], length 0

...

19:21:28.299664 IP 192.168.171.146.1335 > 192.168.171.2.53: 53762+ PTR? 77.215.142.91.in-addr.arpa. (44)

The certificate had this information

subject=/C=US/ST=Virginia/L=Herndon/O=Parallels/OU=Parallels Panel/CN=Parallels Panel/emailAddress=info@parallels.com

issuer=/C=US/ST=Virginia/L=Herndon/O=Parallels/OU=Parallels Panel/CN=Parallels Panel/emailAddress=info@parallels.com

The requests for the PTR requests of the IPs belonging to the command and control domains resulted in an extra set of domains to watch : 216-70-228-110.static-ip.telepacific.net, cba.pl, vm7213.filnet.es and ns1.evs23.com.

(smartoptionsinc.com)

110.228.70.216.in-addr.arpa domain name pointer 216-70-228-110.static-ip.telepacific.net.

(ppc.cba.pl)

65.144.211.95.in-addr.arpa domain name pointer cba.pl.

(cargol.cat)

213.7.149.217.in-addr.arpa domain name pointer vm7213.filnet.es.

(bikeceuta.com)

77.215.142.91.in-addr.arpa domain name pointer ns1.evs23.com.

Details of the network capture

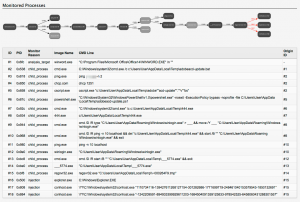

I used tshark to get statistics on the TCP conversation. Note that in the output below I omited the traffic that had to do with normal Windows network behavior.

tshark -r xp.pcap -q -z conv,tcp

================================================================================

TCP Conversations

Filter:<No Filter>

| <- | | -> | | Total | Relative | Duration |

| Frames Bytes | | Frames Bytes | | Frames Bytes | Start | |

192.168.171.146:1334 <-> 91.142.215.77:443 533 796640 107 6331 640 802971 424.351847000 1.2458

192.168.171.146:1328 <-> 95.211.144.65:443 10 4705 8 978 18 5683 413.780151000 0.1197

192.168.171.146:1322 <-> 216.70.228.110:443 9 2164 8 881 17 3045 407.294957000 1.4385

192.168.171.146:1331 <-> 217.149.7.213:443 8 1602 7 805 15 2407 419.065658000 0.2508

This output of tshark proofs that the communication consisted of

- the first 9 frames with smartoptionsinc.com

- then 10 frames with ppc.cba.pl

- then 8 frames with cargol.cat

- and finally 533 frames with bikeceuta.com

In total there was a download of approx. 800 KBytes from the Spanish host bikeceuta.com. That’s more than enough room for a decent payload!

I could not see network traffic to other hosts.

What was downloaded?

Because the traffic was https it is not immediately obvious to see what was downloaded.

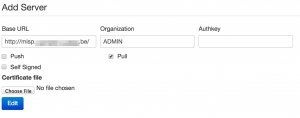

One way you can solve this is by setting up an HTTPS-proxy and basically performing a MiTM attack (with a fake certificate for the four command and control sites). I did not do this but used Google search to verify if I could find references for ‘https’ and any of the four sites.

Based on the information at urlquery.net for bikeceuta.com and urlquery.net for cargol.cat there were requests found for bikeceuta.com/templates/nero.tar.gz, cargol.cat/IESABP/hello.tar.gz and cargol.cat/IESABP/nero.tar.gz. So nero.tar.gz and hello.tar.gz is something to keep an eye on. Be warned, “nero” is also an app for KDE. It’s not a very popular package so blocking it will not cause that many issues but it’s something to take into account when reviewing alerts.

Conclusion

The initial goal was to describe a thought process for extracting IOCs for an ongoing incident. This was relatively easy by analysing the e-mail source, using basic Linux commands and having the malware run in a non-networked virtual machine and capture the outgoing network activity. Additional behavior analysis was afterwards done with running the malware in a networked virtual machine.

Uploading the file to Virustotal for further analysis is a quick way for getting extra information but sometimes this is not possible or advisable. By uploading the file you are basically giving away to the “bad guys” that you are doing an investigation, for some malware samples this is not the right thing to do.

Remarks

The message was received early February (4-February 2015). On the date of the analysis (about 20 days later) it was still possible to activate the ransomware via one of the hardcoded command and control domains.